This blog is republished from the Chronicle of Philanthropy. https://www.philanthropy.com/article/It-s-Time-to-Bring-Back/246849

Sometimes the simplest messages can communicate the most profound truths. I was reminded of that recently during a visit to Montgomery, Ala., for the Presidents’ Forum on Racial Equity in Philanthropy, a conversation with other foundation CEOs about how we and the institutions we lead can do more to curb racism and racial disparities.

The highlight of the gathering was a visit to the Legacy Museum and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice. In a surprisingly compact space on the site of a holding pen where whole families were once prepped for sale and torn apart, the museum tells the devastating story of racial oppression in America, a four-century journey launched in slavery and culminating most recently in mass incarceration.

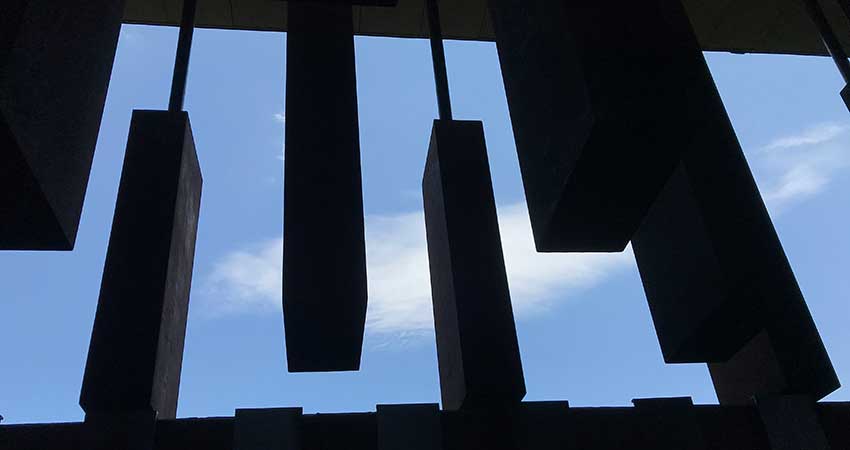

The memorial depicts one of the decades-long stops along that journey: an era of racist violence designed to terrorize African-Americans into servitude, submission, and flight. I cannot imagine how any open-hearted person could stand beneath the heavy iron boxes hanging like upended coffins overhead, each representing a county where the lynchings etched on its side occurred, and not at least sense, deep in their gut, why acknowledging the value of black lives is such a long overdue requirement for our country. America itself should take a knee, in protest and in penance.

But it was a small placard in the museum that most nagged at me after my time there. The sign recounted the early rationale for perpetuating institutionalized slavery in America — that it was necessary to the economy of the South, vital if the country was to meet its rising demand for cotton, tobacco, and, of course, the profits they brought.

That was hardly a revelation, but it haunted me in the context of all that followed deeper in the exhibit. America’s bloody Civil War, the rise of white supremacy as an American creed, Jim Crow, the lynching of thousands, the deliberate terrorizing of whole populations, the voter suppression, the rampant imprisoning of black men, the brutally shortened lives, the wasted human potential, the enduring stain on the nation’s character, all the way down to today’s white-nationalist terrorism and the politics of racial fear-mongering. All of it — every lousy, sad, soul-crushing bit of it — had its origins in an economic argument, the specious contention that an immoral choice was the price of commerce.

We arrived here by self-serving delusion; we arrived here as a business decision.

That Faustian bargain, rightly described as "America’s original sin," is by far the most horrifying and enduring moral tradeoff we have made as a nation in our short history. But what should also strike us now is how often we still fall prey to the same easy temptation, the same morally flawed logic about the need to trade away social goods for commercial gain in the name of economic necessity.

The Price We Pay

It is a habit ubiquitous in our culture. Pollution and its harmful health impacts are just the price we pay for prosperity. Minimum wages so low workers can’t support themselves let alone a family are just the price of the modern economy. Mass shootings are just the price we pay for our freedoms. Plastics trashing the planet are just the price we pay for modern life. The stripping away of privacy is just the price of our technological convenience. Lack of health care for millions is just the price of quality care for the rest of us. Morally repugnant treatment of immigrants and refugees is just the price of protecting American jobs.

A living wage? Health care for everyone? Ending our dependence on fossil fuels? Genuine protections against bias and discrimination? Critics of such measures rarely attack them as unworthy in principle (until recently, at least), preferring instead to label them as "unrealistic." They are fine in theory, the self-appointed realists tell us, but impossible in practice — bad for business, risky for workers, costly for consumers, unaffordable for taxpayers.

This isn’t new. Repeatedly throughout our history we have been told, and for long stretches of time we have believed, that unsafe working conditions, dangerous products, contaminated food, dirty air and water, and grinding generational poverty are all just part of the deal. Yet time after time, when policies and expectations have shifted and unleashed innovation, we have discovered that the supposedly essential and "baked-in" was little more than a failure of imagination.

So, knowing that, why do we persist in clinging to a grim calculus that so readily excludes social goods from its estimations of worth? We can point to the ascendancy of market thinking in our culture, so pervasive now it has convinced us to monetize virtually everything. We can certainly blame the economist Milton Friedman and the triumph of his view that the only responsibility of corporations is to "maximize shareholder value." We can also condemn the powerful interests who benefit from that by exploiting the rules they write to lay claim to ever-growing piles of more.

But a more honest accounting will also look in the mirror. One of the more striking questions posed to my group of foundation CEOs in Montgomery was, "What are the stories you tell yourself about race? And what are the stories you don’t tell?"

'Not Many Killed'

One of the stories we as individuals and as Americans don’t like to tell about ourselves is how often we acquiesce to noxious tradeoffs for the simple reason that we believe they don’t affect us, that we aren’t the ones paying the price. Someone else is at risk, usually someone much poorer and of color. It is their health, schools, opportunity, well-being, or communities that will be sacrificed at the selfsame altar of privilege at which perhaps we ourselves worship, and over time, like plantation owners learning to justify an economy built on owning people, some part of us comes to view it as their fault, a failing in them.

The failing, however, is in us, in what we choose to believe is necessary. As I walked around the Legacy Museum, experiencing its painful recounting of a still-living history, I kept thinking of a headline that appeared in a British newspaper years ago: "Major Earthquake in Guatemala — Not Many Killed." That headline spoke volumes about how shruggingly indifferent we can sometimes be to the pain of others we view as unlike or separate from us. Sure, maybe something unfortunate happened, but not to me or my people, not here, not now, so it really wasn’t that bad, no big deal.

Today that headline feels almost like a statement of official U.S. policy. The pain of refugee children separated from their parents at the border, of communities exposed to toxins by indifferent companies, of parents and teachers worried about the next school shooter wielding an assault rifle, of families terrified of what might happen if their children are stopped by police. The official response is a collective turning-away, its puerile anthem a cynical "Whatever. That’s just how it is. Tell it to someone who cares."

Those of us working in the social-change arena must do more than be horrified by that indifference and its transactional view of pain we ourselves inflict. America has always struggled with racist, misogynist, elitist, and nativist tendencies to rationalize the pain of others we label "less than." But at our best, that self-centered mean-spiritedness has been in dynamic tension with a nobler civic impulse to treat others as we would ourselves, to share rights and privileges more broadly. That impulse, fueled by a thirst for justice, is what has impelled us forward through sometimes violent, always painful eras of emancipation, women’s suffrage, broadening civil and human rights — and the retrenchment that has inevitably followed them.

Stakes Are High

It is our job to help resurrect that impulse now. The stakes today are higher than ever because they are more universally shared and more direly unpredictable. Support for American democracy and the institutions that sustain it is wavering. Climate change is confronting us with challenges that will make a mockery of our dreams of safe havens for the privileged. If the future can be certain to deliver on one truth, it will be the truth of our connectedness.

What America needs most today is a better story. For centuries, we have told ourselves a fiction — that out of painful necessity in a harsh world, someone else’s diminishment is the justifiable price of our success. But every time we tell ourselves that story, we succumb to the same lack of imagination that hampers anyone trapped inside a seemingly compulsory status quo. And, just as critically, we succumb to a lack of empathy — the inability to see ourselves in the suffering and yearning of others — that we can no longer afford in the world we are now entering.The story we need today will flip the old story on its bitter head: Out of great necessity in a harsh world, we will only succeed by banding together, by protecting the vulnerable because we are all vulnerable, by demanding equal justice for all because without it we will all suffer. It is the story of shared responsibility and mutual caring that lies at the heart of civil society. It is ours to tell, and it is high time we started telling it.

Written by:

Grant Oliphant

President