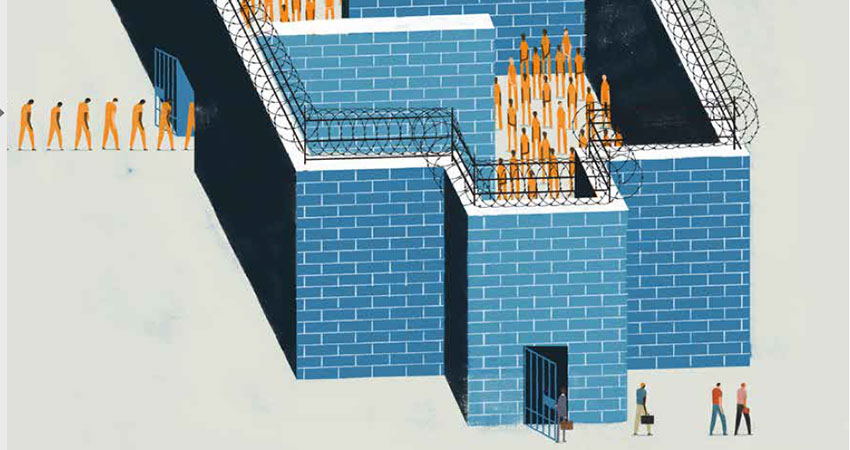

The following essay by Heinz Endowments President Grant Oliphant also opens a special issue of our magazine, h, that explores criminal justice reform in America. The stories examine efforts to change different factors that affect the country’s justice system, such as school discipline policies, police practices, cash bail procedures and opportunities after incarceration. Included among the articles are the personal accounts of people who have experienced a flawed system that often seems far from just. This issue of h is on our website, and printed copies will be available by the end of the month.

"What percentage of people in prison today are there for violent crimes?”

The activist DeRay Mckesson stared expectantly across the table at me. I was interviewing him for The Heinz Endowments’ “We Can Be” podcast, but DeRay, host of “Pod Save the People” and a Jedi master at this craft, had deftly and swiftly turned the tables on his host.

“Twenty percent?” I guessed, embarrassed not to know the precise figure.

“Eight percent,” he corrected.

He wasn’t just toying with me — he was making a point. The more we believe that people in prison are violent and dangerous, the more inclined we are to accept the nation’s bulging prison populations and costs, along with the mass incarceration of black and brown people, as somehow necessary for public safety.

Thankfully, over the course of the past decade, that tragically misbegotten narrative has been increasingly disrupted by pioneering thinkers and activists like Michelle Alexander and Bryan Stevenson. They have highlighted how disparate laws and enforcement approaches, many rooted in nothing more than racism on the one hand and the protection of privilege on the other, have resulted over time in wildly disproportionate rates of incarceration for people of color.

They have called attention to the vast numbers of people ensnared in the criminal justice system who have been found guilty of minor crimes — or, stunningly, of no crime at all — but who cannot find their way out because their poverty keeps them from paying the draconian fines, bail and bonds that lock them in place and deprive them of any hope of a livelihood. They have demonstrated how a system that claims to be fair and impartial instead has been almost perfectly designed to discriminate against people based on skin color, disability, gender orientation and economic status.

As Darren Walker, president of the Ford Foundation, told me recently during a conversation about disability rights, a decade ago society largely took the phenomenon of mass incarceration as an unfortunate but necessary given. Today, however, that narrative is changing.

A growing number of people — including, critically, some policymakers, commentators and law enforcement officials — are recognizing mass incarceration for what it is: racist, unfair, and a terrible waste both of taxpayer resources and of human potential. That’s why, today, there is a bipartisan movement to end mass incarceration, because responsible people on both the political right and left agree that the system as it currently functions must be reformed.

But let’s be clear: Myths die hard.

So much of America’s criminal justice system as it exists today is driven by the threefold, closed-loop logic of fear, racism and indifference. Why has a freedom-loving country become the developed world’s most aggressive jailer of its own people? Why have Americans tolerated the staggering costs of a voracious and self-perpetuating prison industrial complex?

The data tells us it is not because of worsening crime. Nor is it because the system is remotely effective in improving the lives and behaviors of those who pass through it.

We have tolerated it out of fear. We have been led to believe, or chosen to accept, that violent crime is pervasive in our society, even though, to DeRay Mckesson’s point, it isn’t. That fear, abetted by opportunistic politicians exploiting it for political gain, convinces us that only ever more draconian laws (“Three strikes! No, one strike! Just lock ’em up!”), life-ruining practices (“Who cares if they can’t make bail and get to work — that’ll teach ’em!”), and swelling prison populations and costs (“Let ’em rot!”) will protect us. In the face of danger, any harshness, no matter how pointless, feels appropriate and satisfying.

We have tolerated it, too, because in America a largely white governing majority, steeped in centuries of white supremacist orthodoxy, has too easily associated “dangerous” crime with race. Early in the failed “war on drugs,” which has ruined far more lives than it has saved, crack cocaine use, which was more prevalent in the black community, was criminalized to a level unseen for powdered cocaine use, which was more common in the white community. Today’s opioid epidemic shifted from being treated as a crime problem to a public health crisis only when its deep reach into white America became clear. The fascination of policymakers in the 1990s with so-called “super predators” played on fears of young black men, and policies like stop-and-frisk legitimized racial profiling. Black defendants get harsher sentences and higher bails than white defendants charged with similar crimes. This is what institutionalized racism looks like.

Finally, we have tolerated it out of indifference. The financially well-off can afford to be unconcerned with a system whose abuses target the poor. White people can afford to be unconcerned with a system whose abuses target people of color. We are not a society that easily connects the dots from another person’s or group’s experience of injustice to a diminishment of our own lives.

To truly reform America’s criminal justice system, we are going to have to do the hard work of untangling ourselves, bit by angry bit, from the vicious snarl of the fear, racism and indifference that has shaped it. Nowhere is that more evident than in what sociologists call the “school-to-prison pipeline.” As research supported by the Endowments has demonstrated, even in preschool black schoolchildren are disciplined, suspended and expelled at rates far higher than white children, an obviously unjust dynamic that increases their likelihood of colliding with the justice system.

But that is just one of many manifestations of a system in desperate need of reform. Our colleagues at the Ford Foundation have focused on building a national movement to end mass incarceration. The Joyce Foundation is supporting better policing while taking on gun violence and the system that perpetuates the too-easy availability of deadly firearms. The MacArthur Foundation is seeking to make local justice systems fairer and reduce local jail populations, including funding a redesign of the jail here in Allegheny County. Reforming the criminal justice system will require all of these changes and more.

Most fundamentally it will require a change of mind and a change of heart. The change of mind is to replace our knee-jerk tendency to “get tough” as our perpetual response to crime and to focus instead on whether policies are actually effective. In his work with young people, the Pittsburgh activist and rapper Jasiri X teaches that “truth is our only rule.” Adults should be brave enough to adopt the same rule in our criminal justice policies, relying on data and science to guide us.

The change of heart is to remember, as Darren Walker has stressed in his work at Ford, that a crucial element of justice is redemption. In our society, in our democracy, and in our many faith traditions, we believe in the possibility of people coming back from a mistake and rebuilding their lives. At an even deeper level, the change of heart is to understand how a system that robs any group of dignity or hope will only feed our collective divisions, paranoia, and all the human and financial costs that come with that. We are not strengthened by robbing others of their dignity; we are only made smaller.

Myths die hard, but we can change them. Today’s activists echo a question asked by their civil rights forebears: “Which side are you on, my people? Which side are you on?” The answer, of course, is that an America — and a Pittsburgh — worthy of its ambitions in the end must be on the side of those who suffer from injustice. Which is not someone else’s side, ultimately, but mine too, and yours as well.

Written by:

Grant Oliphant

President