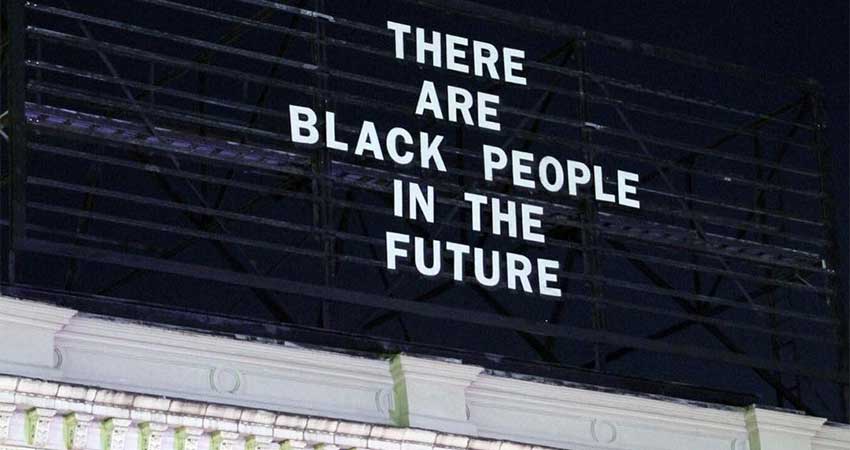

In the Pittsburgh neighborhood of East Liberty, which many Pittsburghers view as ground zero in our city’s burgeoning struggle with gentrification and displacement, the artist Alisha Wormsley recently injected a wryly brilliant note with her billboard declaring: “There Are Black People in the Future.” Better commentators than I — read Damon Young in Very Smart Brothas or Tony Norman in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette for a sense of the community reaction— have responded to a decision by the billboard’s landlord to remove the work because she had reportedly received complaints that it was “offensive” and “controversial,” a decision that has now apparently and fortunately been reversed. I simply want to add three observations.

First, I had my own run-in with the billboard’s curator, Jon Rubin, years ago, and despite my own passion for free speech, I got it wrong. Here’s what I learned from that experience: You can’t nuance artistic freedom. Criticize an artist’s work all you want, but if you provide a space for art, support art, or simply believe in the role of art in human society, then you have to stand with the artist’s right to free expression come what may. The alternative is to consign not only artists but the rest of us to a paint-by-numbers world where the only measure of value is conformity with some presumed, homogenized, blandly acceptable norm.

Second, the alleged discomfort with Wormsley’s work is deeply telling. The genius of her simple declarative lay partly in how it challenged viewers to think why such a statement of the obvious might be necessary in the first place. In a few words and an astute use of context, it invoked critical questions about race, economic disparity, urban design, history, and who our city is for, now and in the future. And the reaction to her piece dramatically proved its point. We are so insanely afraid of dealing with these issues honestly and openly that we can’t even bear for an artist to observe the mere fact of race. That has to change or the future will be good for no one.

Third, the broader brilliance of Wormsley’s piece is how it reflects not only on a local dynamic but also on a deepening national policy of erasure. America has a long and shameful history of deliberately drawing African Americans and other minorities outside the lines of social benefit. But what is happening now is striking for its audacity and scale. To take just one example, our upcoming national census — the critical count that determines everything from the flow of federal money to representation in government — will, unless something happens, deliberately undercount millions of people. That’s a euphemism for “not count,” as in, you don’t count. And of course that’s the point.

In an email exchange we had yesterday on Wormsley’s piece, an African American member of the Endowments’ staff drily commented, “I’m just relieved to know there will still be black people in the future.” Like most humor, her comment carried a powerful message. In the years to come, will we live in a world embracing of difference, devoted to equity, caring about others? Will we live in a world where we, whoever we are, count? It’s an open issue, and the answer is very much up to us.

Written by:

Grant Oliphant

President